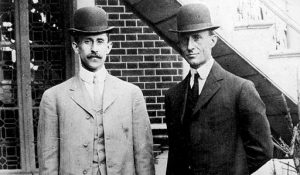

Wilbur Wright (1867 – 1912)

Orville Wright (1871 – 1948)

Invented powered flight

Enshrined: 1985

Home Town: Wilbur: Millville, Indiana, Orville: Dayton, Ohio

Youth Activities: Became interested in flight when their father gave them a small helicopter-type toy powered by a rubber band. The brothers built their own versions of the toy, but found they could not easily develop a larger, heavier version that could actually fly. They put this problem aside for a time.

High School:

Wilbur: Attended Richmond (IN) High School

Orville: Attended Dayton Central High School

Engineering and Science Achievements:

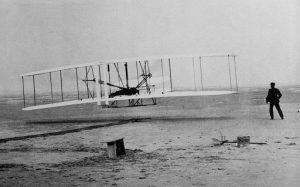

As Wilbur and Orville Wright described it, the December 17, 1903 initial flight of the their flying machine was

“. . . the first in the history of the world in which a machine carrying a man had raised itself by its own power into the air in free flight, had sailed forward on a level course without reduction of speed, and had finally landed without being wrecked.”

Had the Wright brothers never been born, someone else would have eventually developed a successful heavier-than-air flying machine. That it happened when it did, however, was a testament to the Wrights’ physical courage, analytical acumen, mechanical know-how, and dogged pursuit of excellence through the scientific process of trial and error.

Inspired by the work of the late German glider pilot Otto Lilienthal (1848-1896), who died when he lost control of his glider and crashed, the Wright brothers took up the question of flight in 1899. Working out of their bicycle shop in Dayton, OH, they advanced the budding field of aeronautics from infancy to where, by 1903, they had established the basic design elements of manned, heavier-than-air, controlled powered flight, including many technology elements that are still employed today. It had all been accomplished in little more than four years of design and experimentation at a material cost of around $1,000 (approximately $25,000 to $30,000 in 2016 dollars), all of which came from the brothers’ own funds.

As they set out on their quest, the brothers didn’t necessarily have a clear vision of where they were headed. In an 1899 letter to the Smithsonian Institution requesting material on aeronautical research, Wilbur stated his desire to “add my mite to help on the future worker who will attain final success.” Indeed, their initial attitudes may have been even more casual. As they indicated in a 1908 article,

“We had taken up aeronautics merely as a sport. We reluctantly entered upon the scientific side of it. But we soon found the work so fascinating that we were drawn into it deeper and deeper.”

The brothers followed an evolutionary course in the development of their first powered aircraft, starting with testing a kite in Dayton in 1899; progressing to kites and gliders tested at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina area from 1900-1903; and culminating in the first controlled powered flights in 1903. For these experimental flights they chose Kitty Hawk, located on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, in order to capitalize on its remoteness for privacy, its steady windy conditions needed to enhance lift, and its sandy soil for soft landings.

The four successful flights on that gusty December day at a site near Kitty Hawk known as Kill Devil Hills were modestly brief. The first flight was piloted by Orville and covered approximately 120 feet in 12 seconds. The next two flights were longer—approximately 175 and 200 feet—and were piloted by Wilbur and Orville respectively. The final flight piloted by Wilbur covered 852 feet. There was discussion of a fifth flight, but a gust of wind struck the aircraft, damaging it to the point where further flights were not possible. Nonetheless, the four flights demonstrated that the Wrights had addressed and resolved all of the basic challenges standing in the way of putting a manned, self-powered flying machine into the air; keeping it aloft; and controlling it; most notably:

- Lift and Drag: Conducted wind tunnel experiments to determine the necessary size and shape of wings needed to provide lift required for an aircraft of a specific weight.

- Thrust: Developed and built their own light-weight engine, transmission system, and propellers to provide the power needed to launch the aircraft and sustain flight once airborne.

- Flight Control: Developed a three-axis control system for their aircraft consisting of:

o Pitch: Developed a front mounted elevator (or canard), which is a movable horizontal surface that could be manipulated in response to changes in oncoming airflow to control the longitudinal (nose to tail) pitch of the aircraft. While the initial Wright aircraft designs had been unstable, the pilot-controlled elevator prevented the aircraft from either nosing over into the ground or abruptly losing lift from a wing stall due to large nose-up pitch attitudes.

o Roll: Devised a system of “wing warping” to control lateral balance (i.e., rotation of the aircraft around the longitudinal axis). Wilbur conceived of wing warping while idly twisting an inner tube box at the bicycle repair shop.

o Yaw: Installed a movable vertical rudder to control left-to-right movement of the fuselage along the aircraft’s vertical axis. (The coupling of roll and yaw control became one of the fundamental tenets of the Wright Brothers 1906 patent for aircraft flight control.)

Much work, however, remained to be done. While their craft had indeed flown, the brothers needed to refine their invention to a point where it would be a practical device that could be patented and sold. Key considerations were to demonstrate that the aircraft, which had flown only in a straight line at Kill Devil Hills, could be safely launched, banked, turned, and landed on a recurring basis. To accomplish this, the Wrights returned home to Dayton and conducted an additional two years’ worth of test flights at Huffman Prairie (now part of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base), a site northeast of town whose owner allowed them to use his farm as long as they agreed to move the livestock out of the way before takeoff. The first circular flight was achieved in 1904, and in 1905 Wilbur circled the field 29 times in a single flight. In addition to having dramatically improved their flying machine, the brothers had also taught themselves how to pilot it!

As they had now fashioned an aircraft suitable for practical use, the Wrights increasingly turned to the business side of their enterprise, obtaining patents and seeking customers. The brothers didn’t fly again until 1908, when they successfully demonstrated their aircraft first in France and later at Fort Myer, Virginia. They ultimately secured contracts with the U.S. Army and with French and German commercial firms. While news of their accomplishments had often met with skepticism or outright disbelief, they now became world-renowned celebrities. They established the Wright Company in 1909 to mass-produce their Model B and founded the Wright School of Aviation to train pilots.

Wilbur’s untimely death from typhoid fever in 1912 put an end to brilliant teamwork of the Wright brothers. Orville continued his work in aeronautics, demonstrating an automatic stabilizer (a forerunner of today’s autopilot) in 1913. He sold the Wright Company in 1915 and set up his own consulting firm, the Wright Aeronautical Laboratory. (Ironically, in 1929 the Wright Aircraft Company was merged with Curtis Aircraft, with whom the Wrights fought extensively over patent infringement; today the Curtis-Wright Company continues the legacy of these aviation pioneers.) During WWI, Orville planned the production of an American version of the British DH-4 bomber. In 1918, he gave up flying because of health reasons. The latter years of his life were spent as an “elder statesman” of the aeronautics world, as he served on various boards and commissions, including the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA, which became the forerunner of NASA). By the time of his death in 1948, Orville had witnessed the dawn of the jet age and supersonic flight.

Additional Details:

One would be hard-pressed to name a more effective, synergetic tandem than Wilbur and Orville Wright. Individuals of varying temperaments and talents who could and did succeed independently, they nonetheless chose to share the main threads of their lives—childhood toys, business ventures, scientific inquiry and achievement, even the same bank account. In these things, they seemed to think and act as one. While they were known to argue from time to time, their differences were eventually resolved, and one can assume that their occasional heated exchanges ultimately advanced their progress in whatever issues they were debating.

The Wrights were raised in an enlightened family. Their father, Bishop Milton Wright of the United Brethren Church, maintained an extensive library. He and his wife, Susan Koerner Wright, encouraged their children to be inquisitive and think for themselves. Wilbur and Orville’s sister Katherine Wright, a graduate of Oberlin College and high school Latin teacher, was the only family member to earn a college degree. She was a steadfast source of moral support to her brothers during their aeronautical endeavors.

The brothers set up a printing business in 1889 and branched into bicycle repair and sales in 1892. They first offered their own make of bicycle, the Van Cleve, for sale in 1896. Later, they leveraged their insights on balancing a bicycle in crafting their approach to aircraft control.

Originally an outgoing and athletic youth, Wilbur was seriously injured when he was struck in the mouth by a hockey stick in 1885, causing the loss of most of his upper front teeth. Complications set in, including digestive problems, heart palpitations, and depression. While recovering, he led a reclusive life for the next three years, caring for his dying mother, but also spending a great deal of time reading—a pursuit that helped rekindle his interest in aeronautics. Somewhat more academically-inclined than Orville, Wilbur was a gifted speaker and a superb writer. He served as oral and written spokesman for the brothers and their company.

Orville was the more mechanically-minded of the two. As a kindergartener, he skipped school at a friend’s house for several consecutive days to disassemble and reassemble the friend’s mother’s sewing machine. An introvert, he was uncomfortable with large crowds and refused to speak in public.

The original craft flown at Kitty Hawk is now on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. The craft that the Wrights themselves later described as the first true aircraft, because it demonstrated continuous controlled flight, was actually the third Wright aircraft flown at Huffman Prairie in 1905. It is on display at the Carillon Park Museum south of Downtown Dayton.

References:

Crouch, Tom D., First Flight: the Wright Brothers and the Invention of the Airplane, U.S. National Park Service Handbook No. 159, Washington DC, U.S. Department of the Interior (publication date not provided).

Kelly, Fred C., “Introduction” to Wright, Orville, How We Invented the Airplane, An Illustrated History, New York, David M. McKay Co., 1953, and New York, Dover Publications, 1988.

Kelly, Fred C., “After Kitty Hawk: A Brief Resume,” included in “Wright, Orville How We Invented the Airplane, An Illustrated History, New York, David M. McKay Co., 1953, and New York, Dover Publications, 1988.

“Inventing a Flying Machine,” Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, retrieved 25 August 2016 from https://airandspace.si.edu/exhibitions/wright-brothers/online/fly/index.cfm.

McCullough, David, The Wright Brothers, New York, Simon & Schuster, 2015.

Stimson, Dr. Richard, “The Wright Brothers 1900 Glider Experiments at Kitty Hawk, The Wright Stories, retrieved 1 September 2016 from http://wrightstories.com/the-wright-brothers-1900-glider-experiments-at-kitty-hawk/.

“Wilbur and Orville,” Dayton Aviation Heritage, retrieved 6 September 2016 from https://www.nps.gov/daav/learn/kidsyouth/wilburandorville.htm.

Wright, Orville, How We Invented the Airplane, An Illustrated History, New York, David M. McKay Co, 1953, and New York, Dover Publications, 1988.

Wright, Orville and Wilbur, “The Wright Brothers Aeroplane,” The Century Magazine, September 1908 (vol. LXXVI, no 5, pp. 641-650), reprinted in Wright, Orville, How We Invented the Airplane, An Illustrated History, New York, David M. McKay Co, 1953, and New York, Dover Publications, 1988.

Links:

https://airandspace.si.edu/exhibitions/wright-brothers/online/fly/index.cfm

http://wrightstories.com/the-wright-brothers-1900-glider-experiments-at-kitty-hawk/

https://www.nps.gov/daav/learn/kidsyouth/wilburandorville.htm